At work, as well as in life, stuff happens that you didn't want to happen or weren't expecting to happen. At best, it is inconvenient that it happened, at worse it can have a significant impact across a range of things that matter.

You can either live with this variable outcome pattern, put in place mitigating actions to minimise the impact when it does happen again, or activity investigate why it happens at all.

A root cause is a core issue that is one or more steps behind some type of non-conformance that needs to be removed.

Root cause analysis asks three basic questions:

- What's the problem?

- Why did it happen?

- What will be done to prevent it from happening again?

Cause and effect are interrelated

Investigation usually reveals that the reason why A happened is because B had happened earlier, and B happened because C and D happened at the same time, or some similar chain of events. It is very unusual for an event to happen on its own, with no trigger.

By stepping through each part of the chain, it is possible to work out why the situation now being faced started, or at least use the insight gained to allow an educated guess to be made as to why, and to take some appropriate action to determine if that is the case. If that action doesn't modify the end result, then it is possible to discount that path and try something else, until a solution is found.

Types of Cause

Most causes fall into one of three categories:

- Human causes – someone didn't do something that should have been done, or they did do something, but they did it wrong. For example, the room booking clerk booked the wrong 'Hotel du Palais'.

- Process causes – a Standard Operating Procedure or IT system that guides the user in what to do is incorrect or does not cover the eventuality which caused the unwanted outcome. For example, the room booking system booked the correct 'Hotel du Palais', but failed to notice that it was closed for redecoration that week.

- Material causes – a physical item failed in some way. For example, the Electronic Room Key failed for the room which was booked at the Hotel du Palais', so it was made 'non-available'.

Five Investigation Steps

Whilst it is helpful to know that there are often three types of causes, any investigation won't necessarily focus on a cause type. Rather it is a case of following the steps below and looking for patterns and specific actions that contribute to a problem. There can be more than one root cause behind what is evident.

1. State the visible problem - clearly set out what is causing the impact. This may be one matter, or it may be a collection of matters that together are preventing sales, affecting operations or costing the company money.

- What is the obvious challenge to be solved?

- Are there any particular symptoms?

2. Collect the data - speak to those involved in the problem domain and ask for evidence of what is happening. Aim to triangulate the information gained by using different perspectives.

- What is telling you that there is a problem?

- Is it recent, or has been happening for a while?

- Is it continuous or intermittent?

- What magnitude of trouble does it cause?

3. What could be causing the problem - aim to uncover many possible reasons for the matter to happen. Keep asking 'so what?' and 'why?' to drill down into the detail and to surface facts from assumptions. Don't stop after the first one or two possibilities, but aim to peel back the context for greater insight.

- What sequence of events lead to the problem?

- Are there any particular conditions that are often present?

- Are there any tangential matters that always seem to be happening?

4. Identify the underlying cause(s) - start to build a cause and effect diagram to visualise the information that you are uncovering.

- What are the main reasons that the problem has occurred?

- Why do these problems exist?

5. Propose a solution - analyse your evolving cause and effect diagram for obvious improvement candidates. Model positive and negative effects to each candidate. Consider making a small change to test its effectiveness, then making a further series of small changes.

- What actions can you take to prevent the problem occurring?

- Who will be responsible for implementing the solution?

- Are their any consequential risks to consider?

- How will you check that it really does solve the problem?

Example

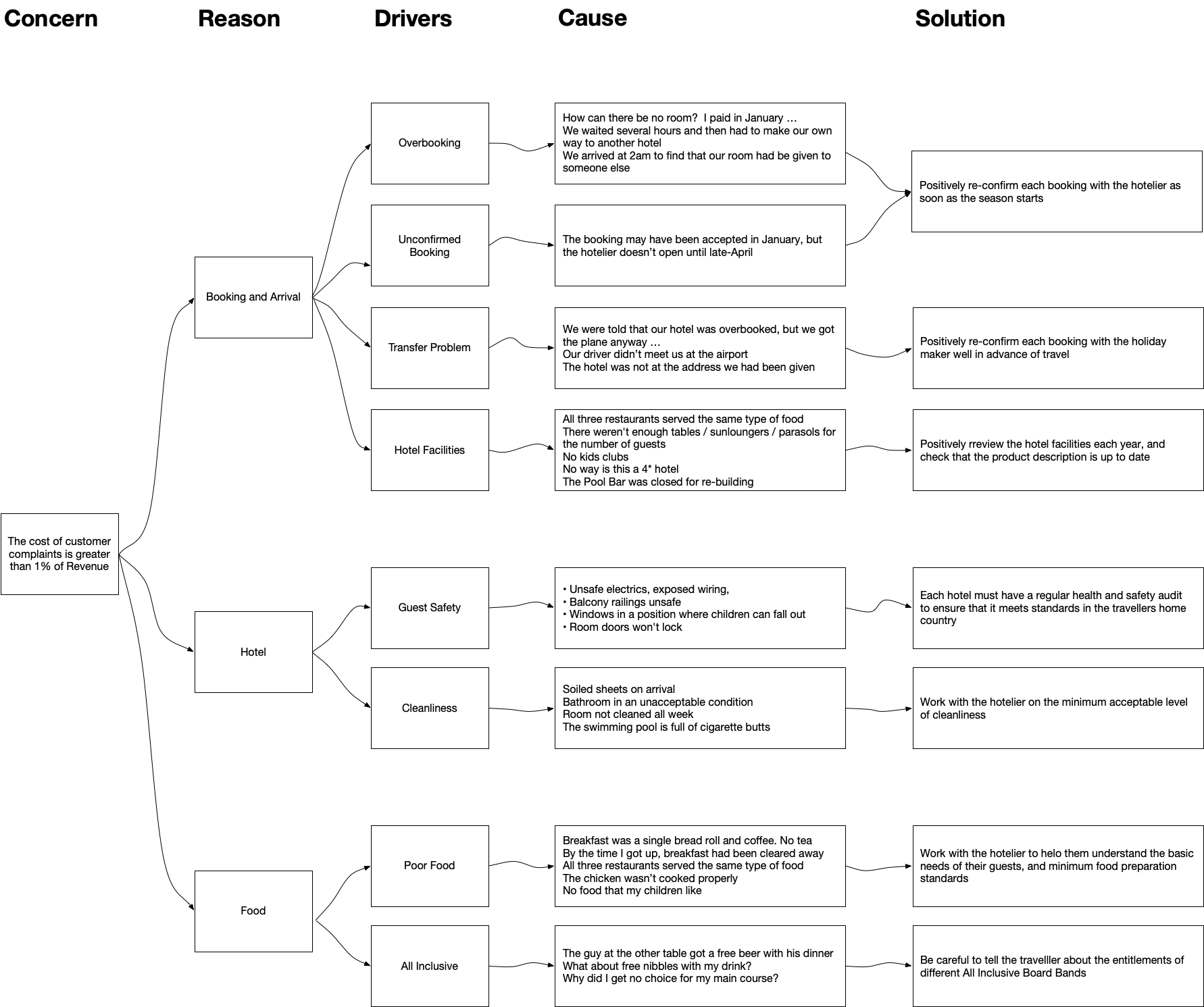

The visible problem is that customer complaints are costing more than an acceptable threshold. By speaking to those involved - in this case the customer complaint call handlers - a picture is built up of the drivers of customer complaints and the underlying causes; all appear to be concerned with the holiday makers' experience. Once these are known, then a number of actions may be taken to reduce the problem, as part of a coordinated solution.

Root cause analysis is a key aspect of effective management. It is far better to find ways of preventing problems, as well as resolving those that actually do develop. There is often a strong business case to support doing so.